Home

[2018]

Home [2018] Tribeca, New York

Exhibition Content

[2018]]

Michael Angel, Home, 2018

Gobbi Fine Art LLC

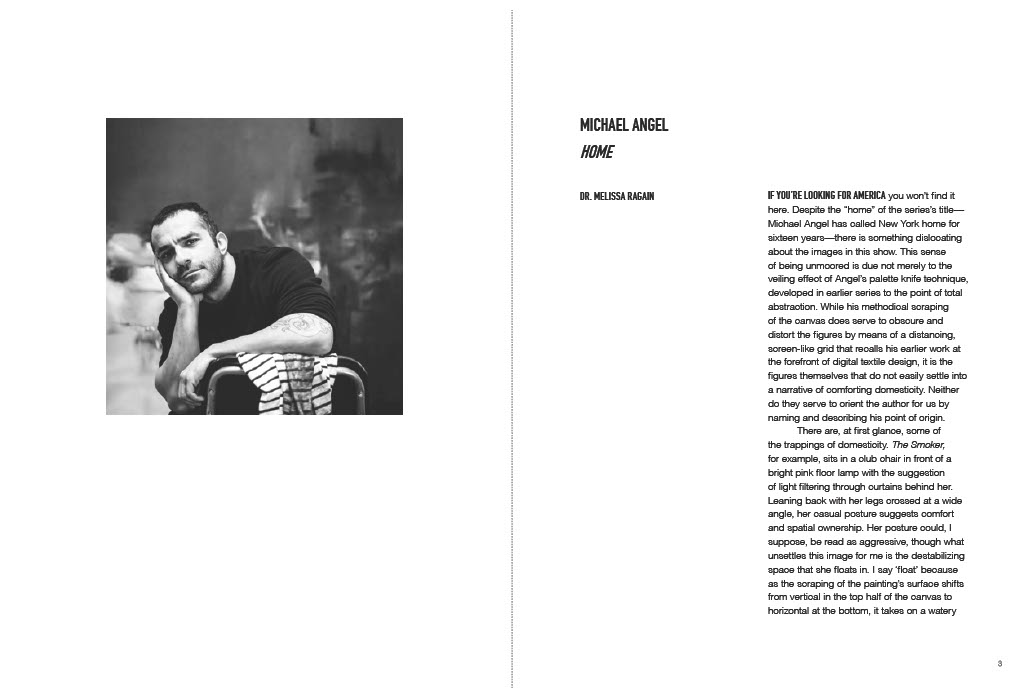

If you’re looking for America you won’t find it here. Despite the “home” of the series’s title — Michael Angel has called New York home for sixteen years — there is something dislocating about the images in this show. This sense of being unmoored is due not merely to the veiling effect of Angel’s palette knife technique, developed in earlier series to the point of total abstraction. While his methodical scraping of the canvas does serve to obscure and distort the figures by means of a distancing, screen-like grid that recalls his earlier work at the forefront of digital textile design, it is the figures themselves that do not easily settle into a narrative of comforting domesticity. Neither do they serve to orient the author for us by naming and describing his point of origin.

There are, at first glance, some of the trappings of domesticity. The Smoker, for example, sits in a club chair in front of a bright pink floor lamp with the suggestion of light filtering through curtains behind her. Leaning back with her legs crossed at a wide angle, her casual posture suggests comfort and spatial ownership. Her posture could, I suppose, be read as aggressive, though what unsettles this image for me is the destabilizing space that she floats in. I say ‘float’ because as the scraping of the painting’s surface shifts from vertical in the top half of the canvas to horizontal at the bottom, it takes on a watery effect, like an image reflected in the surface of a dark lake or cutting out momentarily in a live feed.

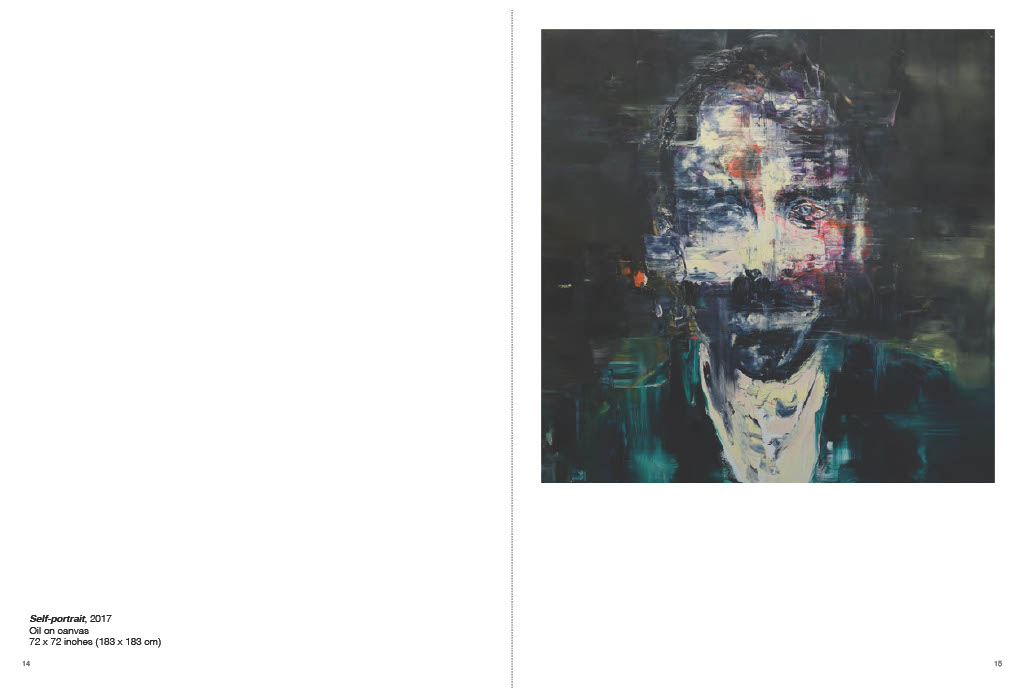

All of Angel’s images from this series have the feel of home as it is revealed through a dark medium. One does not get the sense that these are casual, but rather highly constructed, even guarded, images. His Untitled painting of four figures perched on a sofa suggests an outward-facing image of a family, whose interpersonal relationships remain obscure behind a posturing propriety. While certain of his figures are painted from life, his Self-Portraitfor instance, the majority begin from photographs. Here his personal family photos, like the image of his parents on their wedding day, mingle with found private and commercial images, all dating approximately to the 1960s. Born in Melbourne in 1975, Angel’s contact with the 1960s has come primarily through historical media, whether television reruns from his youth or images encountered much later as an adult.

One cannot help but notice the curious combination of patriarchal authority and Americana that pervades Angel’s source material. The figure of his father in 1969 has a clearly defined profile, while his bride’s face is fully obscured, even with her veil pulled back. Meanwhile, the formless shape hovering behind them (a crucifix perhaps?) creates an ominous presence in what should be a celebratory image. The solitary figure in Untitled II, with his black suit and casual cigarette is the archetypal authoritative man. It calls up the “organization man” who populated the 1950s American imagination, a version of our modern day “men in black,” but its personification of institutional and state authority can also be traced as far back as Max Beckmann’s Self-Portrait in Tuxedo (1927). The source photograph is in fact Rod Serling, host and creator of The Twilight Zone (1959-1964), which Angel would likely have watched with his own father in the 1980s. Likewise, the obscured visage of Saul Bellow in The Conversation manages to communicate, through his power posing and bold color scheme, the self-assuredness of the authorial voice.

The themes of the series culminate in American Beauty and Untitled, which serve as pendants to one another. Both draw from appropriated photographs, one of Gloria O. Smith, the second titleholder of Miss Black America, taken in 1969, and one from an advertisement for White Owl Cigars published in 1965. How are we to understand these images in a series called “Home”? Each presents the viewer with an image of female beauty as an expression of nationhood, though they simultaneously express the power structures that control these deployments of national identity. Miss Black America was started in 1968 in protest against the whiteness of the mainstream Miss America pageant and normative beauty standards that excluded black women. The painting is half covered in a darkness that bifurcates the canvas diagonally, shrouding Smith’s features, except for a few highlights in her hair and earrings, as though splitting the difference between the spotlight she enjoys as a pageant winner and her relative obscurity within American popular culture. In Untitled,a white woman (in the source image, the model Angela Howard) wrapped in the American flag sits bathed in a blindingly white light that encroaches on her face as a series of taches. The contours of her face are lost in the glare except for her heavily lined brows and eyelids. On the one hand, she enjoys a cultural visibility that American Beauty does not. On the other, her passive sexed-up patriotism is hardly liberating; she cannot compete with the self-possession of Smith. Instead she longs for the veneer of authority: “If I were a man,” the original ad copy reads, “I’d smoke White Owl miniatures.”

Much as Angel’s images of family life suggest their orchestration for the outside world, these are not candid images of American life. They are not, for example, those that Robert Frank captured when he visited the segregated America in which these two final source images were made. Instead, Angel’s paintings capture the distance –temporal and emotional – encoded in the originals and bring out the unhomely aspects of experiencing America as home.

Written by Dr. Melissa Ragain

Exhibition Content

[2018]]

Michael Angel, Home, 2018

Gobbi Fine Art LLC

If you’re looking for America you won’t find it here. Despite the “home” of the series’s title — Michael Angel has called New York home for sixteen years — there is something dislocating about the images in this show. This sense of being unmoored is due not merely to the veiling effect of Angel’s palette knife technique, developed in earlier series to the point of total abstraction. While his methodical scraping of the canvas does serve to obscure and distort the figures by means of a distancing, screen-like grid that recalls his earlier work at the forefront of digital textile design, it is the figures themselves that do not easily settle into a narrative of comforting domesticity. Neither do they serve to orient the author for us by naming and describing his point of origin.

There are, at first glance, some of the trappings of domesticity. The Smoker, for example, sits in a club chair in front of a bright pink floor lamp with the suggestion of light filtering through curtains behind her. Leaning back with her legs crossed at a wide angle, her casual posture suggests comfort and spatial ownership. Her posture could, I suppose, be read as aggressive, though what unsettles this image for me is the destabilizing space that she floats in. I say ‘float’ because as the scraping of the painting’s surface shifts from vertical in the top half of the canvas to horizontal at the bottom, it takes on a watery effect, like an image reflected in the surface of a dark lake or cutting out momentarily in a live feed.

All of Angel’s images from this series have the feel of home as it is revealed through a dark medium. One does not get the sense that these are casual, but rather highly constructed, even guarded, images. His Untitled painting of four figures perched on a sofa suggests an outward-facing image of a family, whose interpersonal relationships remain obscure behind a posturing propriety. While certain of his figures are painted from life, his Self-Portraitfor instance, the majority begin from photographs. Here his personal family photos, like the image of his parents on their wedding day, mingle with found private and commercial images, all dating approximately to the 1960s. Born in Melbourne in 1975, Angel’s contact with the 1960s has come primarily through historical media, whether television reruns from his youth or images encountered much later as an adult.

One cannot help but notice the curious combination of patriarchal authority and Americana that pervades Angel’s source material. The figure of his father in 1969 has a clearly defined profile, while his bride’s face is fully obscured, even with her veil pulled back. Meanwhile, the formless shape hovering behind them (a crucifix perhaps?) creates an ominous presence in what should be a celebratory image. The solitary figure in Untitled II, with his black suit and casual cigarette is the archetypal authoritative man. It calls up the “organization man” who populated the 1950s American imagination, a version of our modern day “men in black,” but its personification of institutional and state authority can also be traced as far back as Max Beckmann’s Self-Portrait in Tuxedo (1927). The source photograph is in fact Rod Serling, host and creator of The Twilight Zone (1959-1964), which Angel would likely have watched with his own father in the 1980s. Likewise, the obscured visage of Saul Bellow in The Conversation manages to communicate, through his power posing and bold color scheme, the self-assuredness of the authorial voice.

The themes of the series culminate in American Beauty and Untitled, which serve as pendants to one another. Both draw from appropriated photographs, one of Gloria O. Smith, the second titleholder of Miss Black America, taken in 1969, and one from an advertisement for White Owl Cigars published in 1965. How are we to understand these images in a series called “Home”? Each presents the viewer with an image of female beauty as an expression of nationhood, though they simultaneously express the power structures that control these deployments of national identity. Miss Black America was started in 1968 in protest against the whiteness of the mainstream Miss America pageant and normative beauty standards that excluded black women. The painting is half covered in a darkness that bifurcates the canvas diagonally, shrouding Smith’s features, except for a few highlights in her hair and earrings, as though splitting the difference between the spotlight she enjoys as a pageant winner and her relative obscurity within American popular culture. In Untitled,a white woman (in the source image, the model Angela Howard) wrapped in the American flag sits bathed in a blindingly white light that encroaches on her face as a series of taches. The contours of her face are lost in the glare except for her heavily lined brows and eyelids. On the one hand, she enjoys a cultural visibility that American Beauty does not. On the other, her passive sexed-up patriotism is hardly liberating; she cannot compete with the self-possession of Smith. Instead she longs for the veneer of authority: “If I were a man,” the original ad copy reads, “I’d smoke White Owl miniatures.”

Much as Angel’s images of family life suggest their orchestration for the outside world, these are not candid images of American life. They are not, for example, those that Robert Frank captured when he visited the segregated America in which these two final source images were made. Instead, Angel’s paintings capture the distance –temporal and emotional – encoded in the originals and bring out the unhomely aspects of experiencing America as home.

Written by Dr. Melissa Ragain